The Language of Politics

"Politics and the English Language" by George Orwell (1946)

The fast-paced nature of modern communication seems to have an effect on our language use, especially in the field of politics. Interestingly, though, it’s not just in the last decades that the trend came to be noticed.

It’s the author of the essay “Politics and the English Language” who dug deep into the topic: Eric Arthur Blair, commonly known as George Orwell, the author of sensational anti-utopian novels, Animal Farm (published in 1945) and 1984 (published in 1949).

In his essay, Orwell criticizes the declining clarity of English, arguing that its increasing vagueness and imprecision are both a symptom and a cause of political decay. He observes that modern speech—whether through carelessness or deliberate obfuscation—often prioritizes convenience over accuracy.

According to Orwell, many speakers and writers fail to consider the precise meaning of their words. Instead of choosing clear, direct expressions, they rely on tired metaphors, unnecessarily complex phrases, and foreign words to sound refined. This habit not only dilutes meaning but also distances speakers from their own thoughts.

To be accurate requires a careful consideration of what message to deliver and how to formulate it. However, we tend not to use words, phrases and idioms that are concise, but rather longer statements with unnecessary elements.

For instance, you see a fascinating piece of artwork in a museum. “How nice!,” you may think, “I’d love to have it in my living room!”

Using Orwell’s example, one way of expressing your obsession could be (though it may well be old-fashioned for the modern speech): “The outstanding feature of Mr. X’s work is its living quality.” On the other hand, a wordy way to say the same thing is: “The immediately striking thing about Mr. X’s work is its peculiar deadness.” (Here, the word related to death in a full contrast with the lively image seems to give a vague, striking, roundabout and almost artistic emphasis on what you intend to say, which makes it unnecessarily harder to understand.)

But why do we default to such language? Orwell suggests that it’s easier and faster to use prepackaged expressions than to think through our ideas carefully.

This convenience, however, comes at a cost: while we might effectively convey attitude or “emotional meaning” — whether approval or disapproval, likes and dislikes — we neglect precision. As a result, we often fail to articulate what we truly mean.

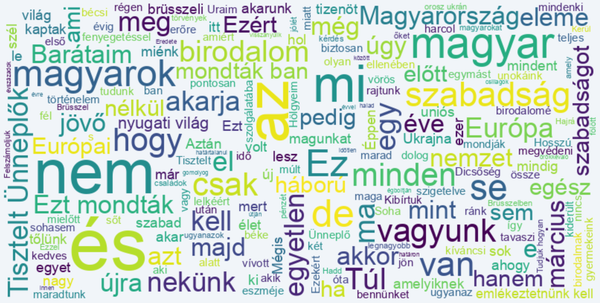

In politics, this tendency is even more pronounced.

The word "democracy" lacks a universally accepted definition, and any attempt to establish one is met with resistance. As a result, supporters of various regimes all claim the label of democracy, fearing that a clear definition would undermine their legitimacy. Such terms are often deliberately vague, allowing them to be used deceptively to manipulate public perception.

While the problems in national governance and international relations, as well as political oppression, have the potential to be avoided, it takes, in Orwell’s opinion, direct and unfiltered honesty, which, nevertheless, doesn’t match the political party's stated goals.

Political language often uses vague and misleading words. Bombing defenseless villages, forcing people from their homes, and burning their belongings is called "pacification." Taking land from millions of farmers and forcing them to leave with only what they can carry is called "population transfer" or "border adjustment." Arresting people without trial, executing them in secret, or sending them to die in harsh labor camps is called "eliminating unreliable elements." With these euphemisms, the political actions are named without bringing up mental images to the audience.

“When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer.”

Orwell brings up an interesting analogy: A person drinks out of a sense of failure, which makes him fail all the more because of the drinking. In the same way, our languages’ “ugliness” and inaccuracy corrupt with thoughts - and also with politics.

By this morning's post I have received a pamphlet dealing with conditions in Germany. The author tells me that he "felt impelled" to write it. I open it at random, and here is almost the first sentence that I see: "[The Allies] have an opportunity not only of achieving a radical transformation of Germany's social and political structure in such a way as to avoid a nationalistic reaction in Germany itself, but at the same time of laying the foundations of a cooperative and unified Europe." You see, he "feels impelled" to write−−feels, presumably, that he has something new to say−−and yet his words, like cavalry horses answering the bugle, group themselves automatically into the familiar dreary pattern.

With his sense of irony, Orwell writes: “One can cure oneself of the not unformation by memorizing this sentence: A not unblack dog was chasing a not unsmall rabbit across a not ungreen field.”